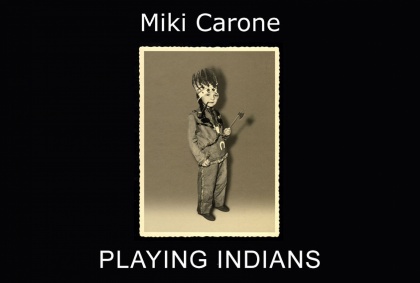

PLAYING INDIANS . Miki Carone, 1975 (English text)

Playing Indians

As a child, I used to play Indians, soldiers and cowboys. The game consisted in making the little plastic soldiers fight against one another by manoeuvring them the way a puppeteer would. Usually, the good guys were white, the pale-faces, and the bad guys were the Redskins, the Indians. I always made the Indians win. I liked their head-dress much more than the soldier’s blue jacket. Their weapons, bows and arrows, more than pistols, guns and cannons. To me, the Indian tepees were much more welcoming than the Fort. The Totem, with all those animals carved and painted one above the other on a tree trunk, to my eyes was much more beautiful than the Crucifix. The tapering canoe seemed to me more elegant than the boat, just as the horse appeared to be more noble and free than the iron horse, the Indian expression for train.

Then, as a boy at school I was taught about the history of Christopher Columbus and the discovery of America. I was told that the Redskins were exterminated because they opposed the arrival of Civilization and Western culture, that the ethnocide of the People of Men (as the Indian called themselves) was inevitable as they refused to integrate and absorb the cultural models of the White Man. In other words, they refused to live, speak, dance, love, eat, work and think as we do. The genocide was thus indispensable as the Indian hindered the advance of Progress. Yet, notwithstanding all these noble reasons, when I went to the cinema to see western films, instinctively I still sided with the Indians and hoped that the Great Spirit would return and also the buffalo to the Great Prairies.

When I grew up, I finally understood why I did not like the Pale-faces and Blue Jackets when I discovered the I am an Indian.

I realized that to survive in the World of the Pale-faces meant trying to create an Indian Reserve in my mind where I could take refuge, a place of encounter with other Indians like myself, to live the way that pleases us following our customs, being able to speak, dance and smoke the calumet together around the fire. I knew that to save my soul and my spirit I never needed to grow up not to become a serious and civil adult. I had to continue being primitive, childlike and play.

Playing, art, creativity and fantasy are the bows and arrows which allow us to dream and make others dream, to wish for other worlds and way of being, living and existing.

Only now that all of this is clear in my mind, after so many years, I wished to describe my child’s game through images.

Miki Carone, 1977